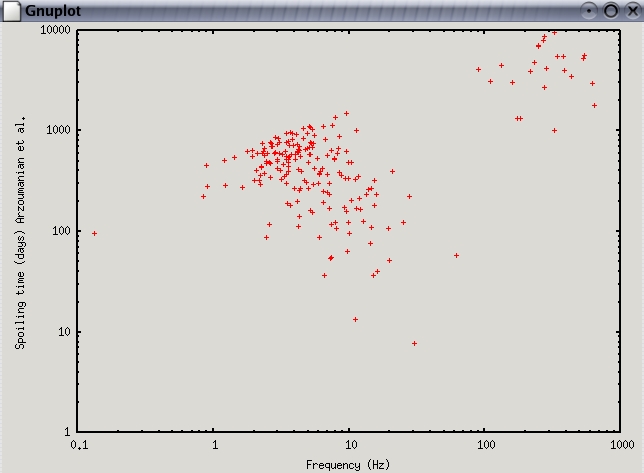

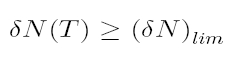

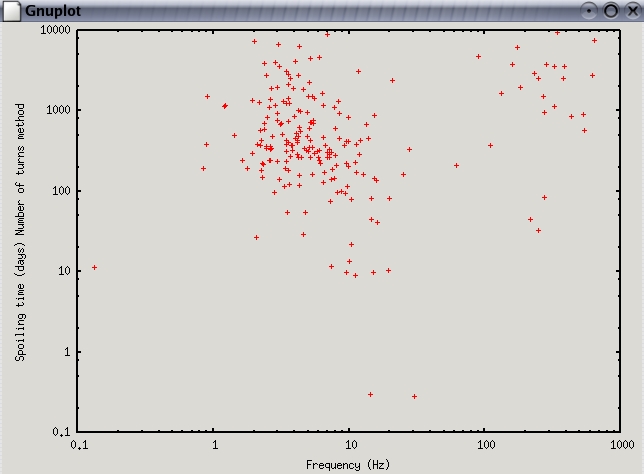

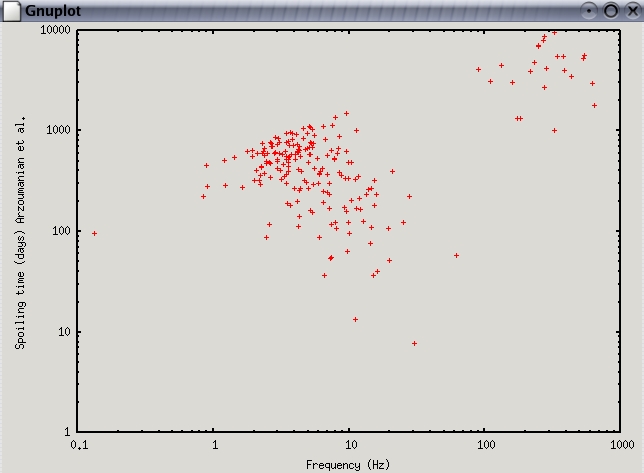

Fig 2

Fig 2

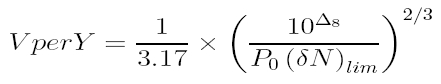

VperY is useful to

evaluate needed telescope time when requests need to be made, but it is

based on the timing noise trend of a hundred pulsars observed by the

Green Bank Telescope. It is necessary to adopt a second method, which

focuses on individual pulsars.